Key Tendencies of 2020

Although one might have expected quarantine limitations to reduce the level of general political activity, in 2020 we faced an increase in the amount of far-right confrontation and violence. It is safe to affirm this being an attempt to reinforce and expand a sort of political and ideological monopoly far-rights have into the realm of the street. On the one hand, this is a clear case of systemic violence against the political opponents openly declared by the far-rights themselves (they call it “safari”). On the other hand, this is an attempt to seize the public space and oust subcultural groups from it. The third tendency of this year is that far-rights consistently disrupted public events organized by left-wing, LGBT+, and feminist-initiatives.

During the local elections of 2020, as well as during the elections of 2019, far-right organizations and groups grew exceedingly active. Even though the electoral success of far-right parties and politicians remains fairly modest, the political activity of these groups during elections becomes more radical. In previous years, various confrontations and attacks on politicians and parties (including both pro-government and oppositional) were rather selective. By contrast, in 2020, far-rights launched, however decentralized, an organized wave of politically motivated street violence.

All the events happening during the campaign Podil is gonna be Right provide another illustrative example of far-right confrontation and violence. In this case, a certain Kyiv district, Podil, became a scene for violence. A few years ago, local authorities pedestrianized Podil, so it became a public space and an attractive rest area for youth. In 2020, under the homophobic and sometimes racist slogans radicals repeatedly attacked young people of “subculture appearance”.

Political “safari” along with ideological war for urban space indicate the attempts of various far-right actors to expand and reinforce their monopoly on organized political violence and censor those who represent other ideologies in the public sphere. It rolls the society back to the atmosphere of the nineties where informally dressed youth could not feel safe, but this time far-rights additionally introduced homophobia. Moreover, the radicalization of political violence poses a direct threat to the evolution of political dialogue.

Methodology

From the beginning of 2020, Marker Monitoring Group has been collecting and systematizing data on street confrontations and violence caused by far-right groups, organizations, parties, and citizens (in 2019, Market made a similar report in cooperation with NGO Institut Respublika). This Monitoring was conducted with support of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung in Ukraine.

The goal of the monitoring Project is to scrutinize the activity of far-right groups in Ukraine and explore the causes and possible consequences of such activity. The end goal of the Project is to develop a database concerning far-right violence and confrontations in Ukraine.

The main method of collecting data is daily monitoring of news on national, macro-regional, local and activist websites and social networks. The results obtained through the monitoring reflect only the part of the far-right street violence that is covered in the monitoring sources. However, the data is collected systematically and therefore allows to:

- assess the scale of the problem;

- track patterns in far-right activity;

- monitor the dynamics of far-right confrontational and violent street activity;

- identify the key actors among the organized far-rights;

- comprehend what kind of social groups have been most commonly victimized by far-right street violence.

Basic Concepts

Confrontation is a protest activity that puts direct pressure on subjects of disagreement but does not aim directly at harming people or damaging property. Confrontation acts include blockage, jostling, seizing one’s premises, or interrupting an event (without resort to physical violence).

Violence is a protest activity aimed at causing injury or damaging property. It should be distinguished between violence aimed at people (attacks, beatings, fights, gunfire, murder, etc.) and violence aimed at property (arson, property destruction, vandalism, etc.).

Overall Monitoring Results

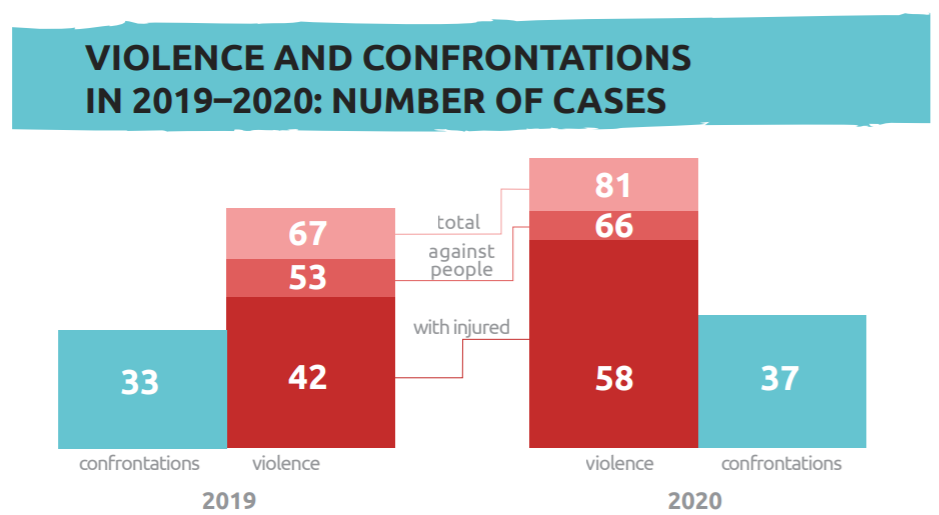

In 2020, the Marker Monitoring Group recorded 118 cases of far-right confrontation and violence, including 37 cases of confrontation and 81 cases of violence, meaning causing injury or damaging property (a complete list of cases you may find attached to Appendix of this Report). 66 cases of aforementioned violence were aimed at people. In addition to 118 cases of far-right confrontation and violence, the Monitoring Group recorded 11 cases of hate-motivated attacks carried out by those who were not affiliated with the Ukrainian far-right movement[1]. These 11 cases are excluded from the overall statistics.

In 2020, there were 14 weeks wherein our Group did not record any case of far-right confrontation and violence. On average, though, there are two cases per week . In this regard, one may assert a certain rise in numbers comparing to 2019, when we recorded 100 cases of far-right confrontation and violence overall. Generally, in 2020, the number of far-right confrontations and violence grew by 18%.

However, the matter is not just that we register an increase in numbers, but that there are certain changes in the nature of these cases. Firstly, in 2020, among all incidents of confrontation and violence, we face a slight increase in proportion towards violence, namely 69% in 2020 compared with 67% in 2019. Secondly, among the cases of violence, there is a slight increase in proportion towards violence against people, namely 81% in 2020 compared with 79% in 2019. In 2020, in 58 cases out of 66 (88% of all cases) casualties were reported amounting to 106 persons, including 18 police officers. To compare, in 2019, casualties were reported in 42 cases of violence aimed at people (79%). To put it another way, a general increment in the number of far-right confrontations and violence entails radicalization as well. That is, a rise of far-right activity on streets with a resort to sporadic violence leads to the situation when this violence is more often directed on people and eventually causes physical injuries.

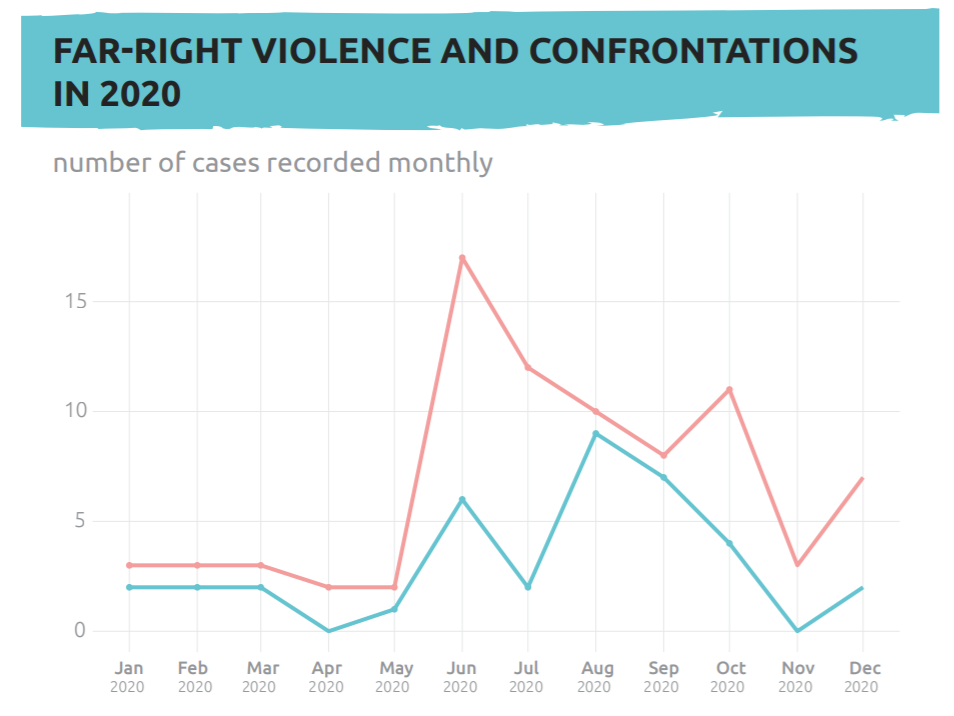

The initial months of 2020 brought us quite a small number of recorded incidents. This may be explained by quarantine measures introduced in Ukraine in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to general decay in political and social activity under conditions of uncertainty and restrictions. The first five months of 2020 allowed us to record merely 20 cases, 13 of which contained elements of violence. However, in June 2020, we faced a rapid increase in the number of far-right confrontation and violence (primarily politically-inclined) aimed at oppositional parties accused of pro-Russian stance and separatism.

Most cases of far-right confrontation and violence were recorded during the summer of 2020, which is quite unusual for Ukraine, for the summer months commonly bring the lull in street activities. Overall, in the summer, 36 out of 56 reported cases (23 in July; 14 in June; and 19 in August) had signs of violence. To compare, during the previous summer we recorded 20 cases altogether. June 2020 set an absolute month record of far-right violence for the whole time of our monitoring activity amounting to 17 cases of violence, 15 of which were aimed at injuring people. In eight of such cases, supporters of Shariy’s Party became the victims; radicals announced a “safari” hunting on them. It did not stop in the following months (more details are provided below).

In 2020, cases of far-right violence and confrontation were most numerous in Kyiv (47 cases), followed by Kharkiv (15), Kherson (7), Odesa (7), Lviv (5), Mykolayiv (4), Dnipro (3), Vinnytsia (3), and Mariupol (3). Two such cases occurred in Zhytomyr, Khmelnytskyi, Nikopol, and Cherkasy. One such episode happened in Berdyansk, Berezne, Derhachi, Ivano-Frankivsk, Konotop, Kramatorsk, Kremenchuk, Kreminna, Liubotyn, Poltava, Rubizhne, Uzhgorod, Zaporizhzhia, Zhmerynka, the village of Pyiterfolvo (Zakarpattia region), and another unknown location.

In 58 out of 118 recorded cases of far-right confrontation and violence in 2020, the participation of specific far-right parties, organizations, groups, or their representatives was reported. At the same time, we have 60 reported cases with either unidentified far-right organizations or conducts conspired by a few participants who do not directly affiliate with a particular organization, yet place their deeds into a general organized far-right framework. For instance, one cannot assert all attacks happening within campaign of political violence necessarily included organized far-right groups; however, when the responsible persons were successfully detained or identified, they occurred primarily from the far-right circles.

Apart from cases where the offending party was identified as far-right, the Report includes cases in which supporting evidence suggest the participation of either far-right members, or far-rights sympathizers. These evidences are the following: the nature of an attack, markings, rhetoric, etc. 11 more hate incidents occurred in 2020, yet they were not connected to the organized far-right movement in Ukraine and for that very reason excluded from our statistics.

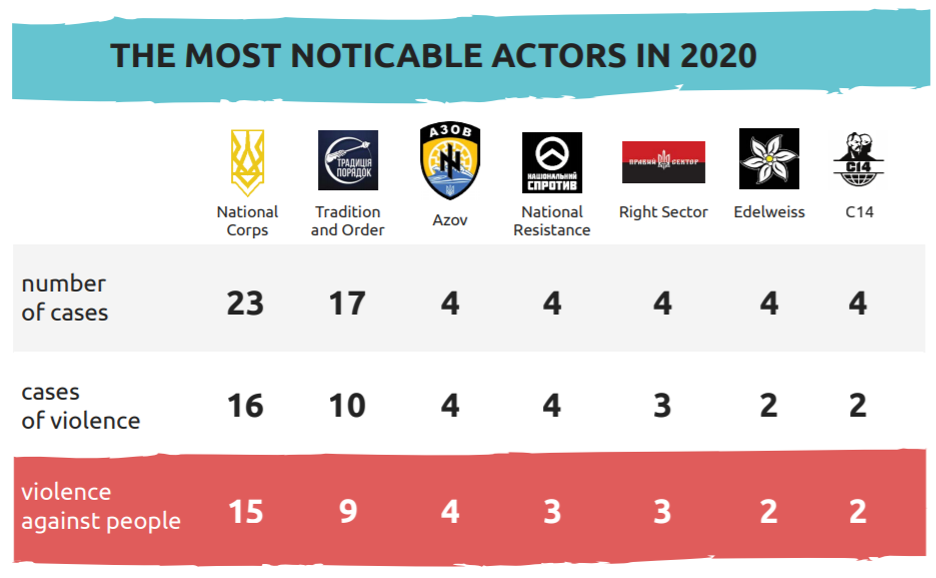

Speaking of cases, where the participation of specific parties, organizations, or groups was reported, National Сorps appeared as the most common actor. It is responsible for 23 cases, including 16 violent cases, 15 of which against people. The second place holds Tradition and Order with its 17 cases, including 10 violent cases, 9 of which against people. When put the activities of these two ‘leaders’ of street confrontation and violence under inspection, a certain “specialization” can be observed. National Corps primarily performs actions against politicians and political parties (16 cases), whereas Tradition and Order prefers to fight with members of LGBT+ and feminists (11 cases), leftists and antifascists (5 cases) as well as with people who have an “informal appearance” (3 cases).

The following organization are responsible for 4 cases each: National Resistance (all cases include violence, 3 of which against people); Right Sector (3 cases include violence, all against people); Edelweiss (2 cases include violence, all against people); C14 (2 cases include violence, all against people); veterans of the Azov movement (all cases include violence and all against people). Next, the following organizations are responsible for 3 cases each: Municipal Guards (2 cases include violence, all against people); National Vigilantes (2 cases include violence, all against people); Centuria[2] (2 cases include violence, one of which against people); Freikor (all 3 cases are violent including 2 against people). Further, organizations below are accountable for 2 cases each: Brotherhood (both cases include violence against people); Sokil (both cases include violence against people); and Svoboda (one case includes violence against people). Finally, one case of violence was caused by Unknown Patriot (violence against people) and another one was Carpathian Sich (violence against people).

Centuria (by 3 cases each); Brotherhood, Svoboda, Sokil (by 2 cases each); Karpatska

Sich, Unlnown Patriot (by 1 case each).

Political “safari”

In 2020, we recorded a total of 51 cases of far-right confrontation and violence against political parties or their specific representatives. By comparison, 2019 produced not more than 19 respective cases. Put it otherwise, in 2020, the amount of far-right political violence increased by a factor of 2,7. In 2020, 18 out of 51 cases were confrontational, while the other 33 included some elements of violence 24 among which were directed at people. An increase in confrontation and violence coincided with the campaign of political violence launched by far-rights and aimed at oppositional parties accused of pro-Russian stance and separatism.

The campaign of political violence was initiated in June 2020 by National Corps and gained its momentum during the election race. In cases when the offending party causing confrontations and committing violence were identified, it consisted primarily of National Corps (16 cases among which 10 against people). In other cases of political confrontation and violence, reports identified other members of the Azov movement (they were veterans of the Azov regiment or members of National Vigilante and Centuria) and C14, Sokil, Right Sector, Edelweiss, Municipal Guards, and Svoboda.

The situation escalated after the demonstration on June 17, 2020, in Kyiv, where the Shariy’s Party demanded an investigation into the attacks on its members. The National Corps, C14, Democratic Axe, and Sokil organized a counter-event where they initiated confrontations, threw eggs at their opponents, and used smoke bombs and tear gas. Police arrested 15 people. Later, in the subway, there were several confrontations between the participants of the demonstration and the far-rights resulting in injuries from both sides. After the demonstration, the far-rights announced a “safari” on social media, calling for attacks against supporters of Shariy’s Party, and even promised a monetary reward.

On June 24, there were three attacks. In Zhytomyr, a veteran of the Azov regiment came to the office of Shariy’s Party cell and beat a local chairman. In Cherkasy, unknown attackers assaulted a chairman of the local Shariy’s Party cell and his wife as well as they beat another party activist. In Kharkiv, on the same day, unidentified individuals beat the chairman of the local Shariy’s Party cell Mykyta Rozhenko with bats; the victim ended up in intensive care. A few hours before the attack, he wrote a report to the police about threats from the local National Corps.

Confrontation and violence by far-rights against representatives of Shariy’s Party unfolded until the end of the local elections in October. People standing on agitational spots of the party were the prime victims of these attacks. One of the late assaults on October 18, 2020, in Kyiv revealed a member of Municipal Ward to be an attacker.

3 cases of political violence included the use of tear gas, 6 cases included a fight or somebody being beaten, and 7 cases included both a beating and a use of tear gas or zelenka (brilliant green Soviet antiseptic, which is difficult to wash away). At least in 2 cases, the use of pyrotechnics was reported, while in the other 3 cases reports identified the use of a bat, a hammer, or a piece of reinforcing steel. Two cases of far-right political violence included gunfire and another one a grenade.

On August 27, nearby Liubotyn on a Kyiv–Kharkiv highway the members of the National Corps and Azov regiment violently shot a bus containing members of an organization named Patriots – For Life . Offenders used traumatic and cold weapons. As a result, 4 persons are hospitalized and 15 attackers detained.

Shortly before elections, other oppositional parties accused of pro-Russian stance and separatism also became victims of the far-right campaign of political violence. These parties include Opposition Platform – For Life and Our Land as well as a few politicians. However, excluding assaults on the organization Patriots – For Life , far-rights preferred to cause confrontations (derailing events, ruining billboards, etc.) or property damage (office raids) while avoiding attacking members and sympathizers of parties.

Overall, 2020 contained 9 cases of attacks on political parties aimed at damaging property, but not harming people. These cases include arson, destroying campaign camps using knives, damaging offices of political parties, etc. In that manner, on August 26 an office façade of Kharkiv cell of Opposition Platform – For Life was damaged and painted in neo-Nazi signs, specifically swastika, Celtic cross, and SS letters.

In 2020, there occurred 18 far-right confrontations aimed at politicians and political parties. These confrontations include painting agitational billboards and party offices, obstructing party events often resulting in jostlement. For example, on June 30 in Kharkiv members of the National Corps threw eggs at Shariy’s Party sympathizers, and on August 24 in Odesa they initiated confrontations with journalists and local councilors from the Opposition Platform – For Life . On October 10, a car rally organized by the Vinnytsia cell of Shariy’s Party was blocked by local far-rights from Edelweiss and Centuria.

Apart from mentioned reports and statistics, in 2020 additionally occurred a considerable lot of ambiguous cases of confrontation and violence against politicians or political parties that we excluded from the Report. These cases failed to provide sufficient evidence of them being caused by far-rights or their sympathizers. Among them, there are 34 cases of violence (2 cases include violence against people) and 59 cases of confrontation aimed at politicians or political parties. Although we excluded these incidents from our Report, we assume at least part of them to be instances of far-right street activity within the political framework. Put another way, a scale of far-right political confrontation and violence might appear even higher than reported above. In all, collected data allows us to claim an unprecedented post-2014 radicalization of political struggle, wherein far-right actors systematically obstruct activities of other political actors and even pose a physical threat to them. In that respect, we affirm that far-rights use street violence to gain influence on political discussion and representation and that it might further entail violence being legitimated and political struggle radicalized.

Wars of Ideologies

The second most frequent situations are cases of violence and confrontation against the ‘customary’ opponents: LGBT+ and feminists, leftists and antifascists. In 2020, 25 cases of far-right confrontation and violence against LGBT+ and feminists were recorded (17 cases include violence, 14 of which were aimed at people). The numbers are slightly higher than in the previous year (when they amounted to 23 cases). We recorder 10 cases of confrontation and violence against leftists/antifascists (6 cases included violence, 5 of which against people). To compare, in 2019, there were 4 similar cases. Moreover, in 2020 there were 14 records of far-right aggression aimed at youth with a “subcultural appearance” (13 cases included violence, all against people), partially motivated by homophobia.

Similar to the previous year, in 2020, a few conflicts occurred during events significant for the feministic and LGBT+ movements. In Kyiv, on March 8 six female participants were attacked on the way back from the demonstration. In Odesa, on August 30 members of Tradition and Order prevented OdesaPride from happening. In the end, 9 people got hurt.

There was violence aimed at the property as well. On February 17, in Kyiv, unknown persons planted the explosives under the office doors of the organization 100% Live (former Network of PLWH). The bomb did not cause injuries to people, yet damaged the doors. These unknown persons left a written message on a crime scene in which they reproved legislation on providing the youth with medical information, whereas an organization Black Block informed about the incident on its channel and threatened journalists who were covering the case. This year, Kharkiv PrideHub stood at least 5 assaults. To provide another example, on December 6 in Kyiv Municipal Guard broke down the doors and pushed into the Otel club deploying tear gas and using homophobic slurs against two persons who were there. The police were there as well but did not attempt to prevent the attack.

At least 10 cases (9 of them included violence) aimed at the youth of “informal appearance” happened in 2020 on Podil in Kyiv and a part of them were racially motivated or of homophobic origin. For instance, on June 19 two such cases occurred. First, members of Tradition and Order and a few other far-rights assaulted three female minors during the “agitation raid”. Before starting the attack, the girls were asked whether they have any affiliation to the LGBT+ community. Next, on the same day far-rights assaulted a group of teenagers who had piercings and painted hair. They were beaten and forced to read out loud some homophobic leaflets. Mass beatings of youth were also reported on September 20 and October 10. Moreover, on December 15 unidentified neo-Nazis using tear gas and rozochka’s (a broken-off bottleneck) injured two guys. During the attack, offenders were yelling “Glory to White Race!”, “Glory to Kyivan Rus!”, and “Faggots”. The police remained uninvolved as usual.

Three cases of far-right confrontation and violence were recorded against left-wing / Antifa activists on January 19, 2020, in Kyiv, when the traditional Antifa demonstration took place. The counter-protest was attended by Tradition and Order and the National Resistance: they threw eggs and fireworks at people gathered on demonstration. 11 attackers were arrested. When the demonstration ended, the far-right visited the office of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung in Ukraine, tore down the sign, and painted the Foundation’s front door. In addition, a confrontation with a person whom the far-right mistook for a left-wing activist was reported; they humiliated and threatened this person.

Apart from that, a few very selective attacks on activists happened as well. On June 19, in Kyiv, unidentified offenders assaulted a girl with Antifa views and poured tomato juice upon her. This attack was reported by the right-wing channel itself. In Lviv, two attacks against one antifascist and eco-activist took place. Local far-rights watched for him on the streets on July 12 and beat the activist, following a successive assault using bats on November 19. Importantly, another attack against the same activist offenders committed on January 19, 2021, this time using tear gas, hammers, and knives.

Organized and Non-Organized Actions Motivated by Ethnic Hatred

Of the 118 cases of far-right confrontation and violence recorded in 2020, 6 cases were related to ethnic minorities and migrants (including 4 cases of violence, one of which against people). In addition, the Monitoring Group noticed 9 more cases of hate-motivated attacks against ethnic minorities and migrants, probably carried out by those who are not affiliated with the Ukrainian far-right movement. That is why we did not include them in the overall stats of the Report (among these 9 cases there were 7 cases of violence 6 of which aimed at people).

Regarding those 6 cases of confrontation and violence against ethnic minorities and migrants counted in our Report, three of them were motivated by anti-Semitism (including 2 violent cases aimed at the property). 7 more hate incidents motivated by anti-Semitism occurred outside of the far-right movement (including 5 with violence, 4 of which against people).

Three cases (excluded from the overall stats) were recorded in Uman. On January 12, there happened a confrontation between Hasidic pilgrims and locals nearby the grave of Reb Nachman. Some sources reported violence, while the police denied it. On August 28, a confrontation between Hasideans and locals occurred, as the latter did not want to let the former into the synagogue. Police opened a criminal case. A few days later, on August 31, four locals assaulted and beat a Hasidiean. Police opened a criminal case.

Among organized attacks motivated by anti-Semitism, it is worth mentioning an attempt on April 20 to set a Kherson synagogue on fire. An unknown person threw a bottle with a flammable mixture at the door of the building. Later, the Security Service of Ukraine reported they took under detention two men adhering to Nazi ideology and ‘celebrating’ Hitler’s birthday in such fashion. They had planned other attacks as well.

A similar occurrence happened in Odesa on June 25, when two persons attempted an arson attack against a mosque on the eve of the Crimean Tatar Flag Day. Security Service of Ukraine managed to detain the offenders and claimed them to be members of a far-right organization. Additionally, case officers declared they suspect agents from a Russian intelligent service had been coordinating the offender’s actions.

In 2020, we also recorder 2 cases of assaults against Roma people. One of them was included in our statistics, but not the other. On April 29, in Kyiv, unidentified individuals broke into a tent where a Roma family lived. They sprayed tear gas, beat the man with a plank, and set the tent on fire. Police opened a case under Part 2 of Art. 161 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. On August 27, in small-town Andriyvka (Kharkiv region) locals tried to evict Roma people, threatened them, and threw eggs and rocks. Aggrieved persons were evacuated by police, but nobody was detained.

Basically, it would be safe to affirm that instances of confrontations and violence against ethnic minorities and migrants as well as hate-motivated crimes are not systemic in Ukraine. Nonetheless, sometimes organized and non-organized hate-incidents happen that might result in violence against people. Moreover, xenophobic and anti-Roma rhetoric has been actively used by far-right organizations to incite ethnic hatred.

Conclusions

Since the beginning of the monitoring (October 2018), confrontations and violence by the far-right were only in some cases directed against ethnic minorities and migrants. Such dynamics, however, should not deceive us about the threat that the far-right movement poses to other groups of people and the democratic processes in Ukrainian society.

The factual monopoly of far-rights on street violence along with police restricting itself from taking action and sometimes even showing indulgence to far-rights are responsible for far-right confrontation and violence within the political and ideological processes. These attempts at cleaning out the Ukrainian political and ideological field and exclusion of some participants employing confrontation and violence are accompanied by selective coverage of the problem by the media and limited attention from civil society. While the anti-Semitic and anti-LGBT+ assaults are widely condemned, political violence often remains overlooked by specialized civil organizations that tend to give offending and injured parties the same amount of voice. This sort of selectiveness commonly finds excuses in personal political and ideological sympathies/antipathies, external factors, or the fact that above problems are “insignificant”. Furthermore, we observe far-right gradual infiltration to civil society institutes, passing off their members as human rights advocates, legitimizing the movement by obtaining grants and by inclusion to security agencies.

At the same time, far-right street actions have been becoming more radicalized, which can lead to an overall radicalization of the Ukrainian political scene. Under conditions of war, pandemic, and general socio-economic instability this sort of radicalization and legitimation of violent methods of political struggle entails additional and quite real threats for the democratic development of the country and its further stabilization.