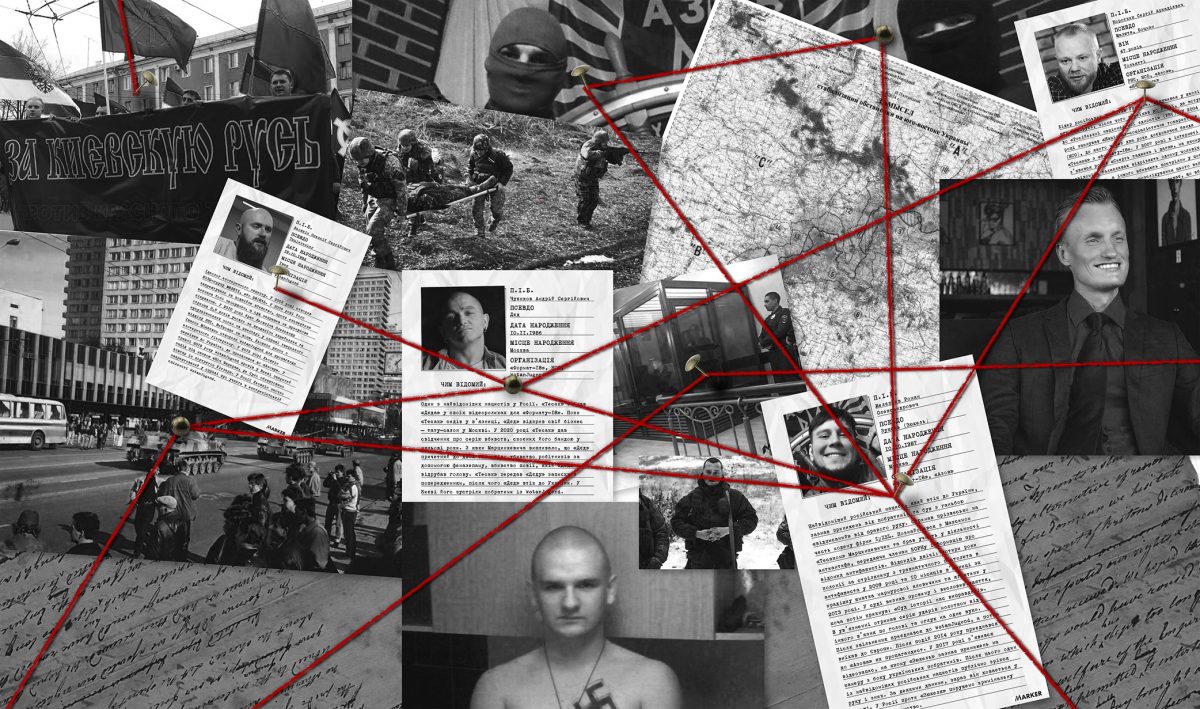

Russian Nazis play a significant role in the Ukrainian far-right movement, even though Ukraine is at war with Russia. The Marker has talked to experts in the field of far-right extremism—journalists, researchers and activists of the anti-fascist movement—and found out which of the Russian Nazis have fled to Ukraine and why.

The Great Schism

The events of 2014—the Euromaidan and the hostilities in Eastern Ukraine that followed—led to a schism among the Russian far-right. Imperialists and Russian nationalists picked the side of the self-proclaimed Donbas Republic, while their former comrades, radical Nazis, chose to fight on the Ukrainian side.

“There was no clear dividing line: the schism also cut through many organizations, meaning that personal preferences played as much of a role as general principles. The trick is in how you view this conflict. If this is a war between Russians and Ukrainians as two nations, then you must support the Russians, of course. But if you think that there is no difference, all of them are parts of the same nation, and the enemies are the West, ZOG (‘Zionist Occupation Government’. Ed.), ‘the Blacks,’ etc., then this war is dangerous fratricide. And then you must either withdraw from it (which was also popular: the division wasn’t into just two parts), or choose the side where you have more opportunities to promote your ideas. And that side is Ukraine, where Azov and the Right Sector are legal and relatively influential (at the time when the conflict started. Ed.). No wonder that those who picked Kyiv’s side were mainly, although not exclusively, radical racists and neo-Nazis,” Aleksandr Verkhovski, the director of the Russian think tank Sova which has been monitoring far-right activities in Russia since 2002, told The Marker.

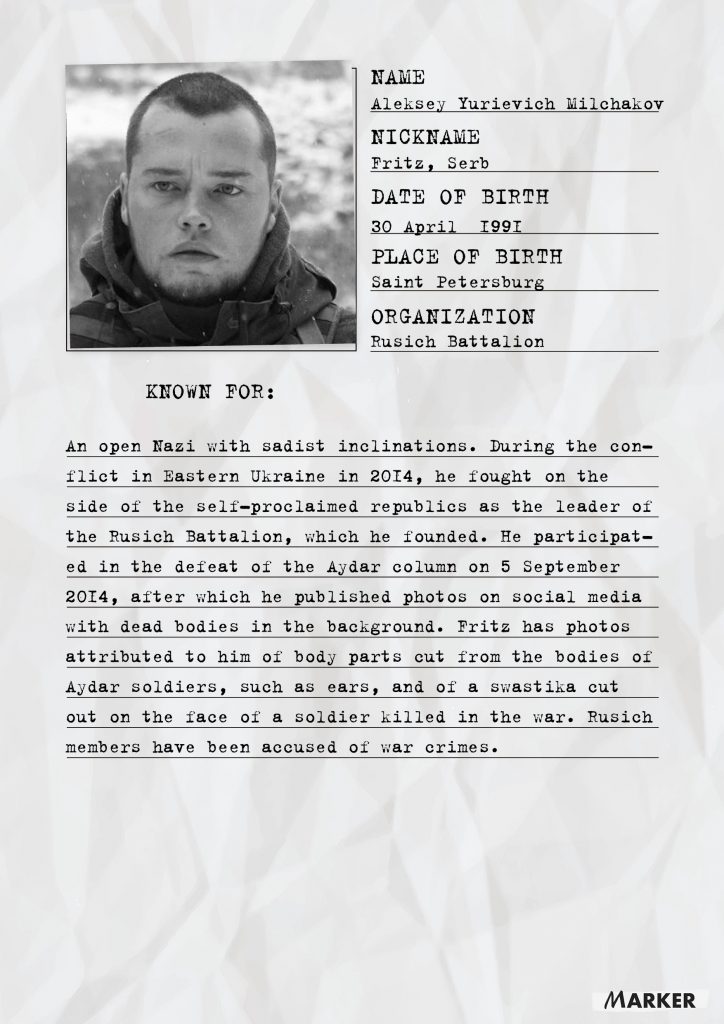

The new face of Novorossia was the open Nazi Aleksey Milchakov. Born in Saint Petersburg, he was a fan of Third Reich symbols known for killing, decapitating, frying and eating a puppy in 2011. He published photos of this act on his VKontakte page. Three years later, Milchakov went to fight in Donbas, where he led the Rusich reconnaissance and sabotage division, which mostly consisted of Nazis.

“Not all of the Nazis chose Ukraine. We saw people from the exact same circle on the opposite side, such as Milchakov and Yan Petrovski. Judging from Milchakov, these are people who, during 2013–2014, were deciding which side to pick in the conflict. Milchakov had been to the Maidan and hung out with his friends who stayed in Ukraine and joined Azov. Milchakov decided to stay on the Russian, imperialist side,” said Leonid Ragozin, a Riga-based independent journalist, in a conversation with The Marker.

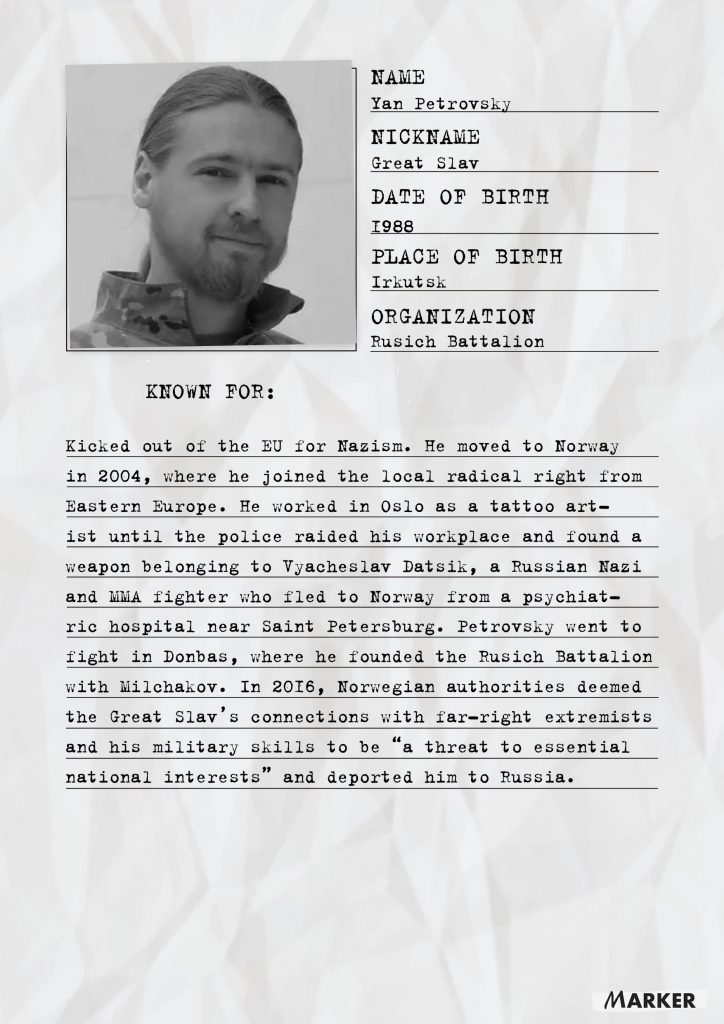

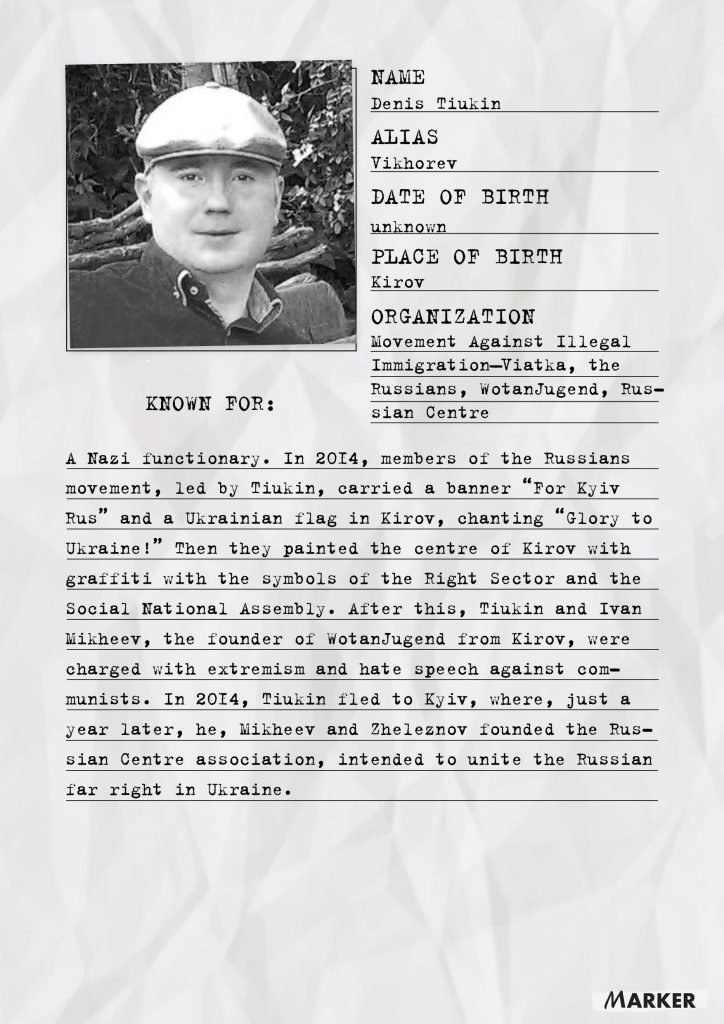

According to the expert, the choice of the side in this conflict became a matter of taste for the Nazis. “In 2015, the Azov radio hosted a long discussion with Milchakov and Denis Vikhorev, a neo-Nazi from Kirov who found himself in Ukraine and joined the Nazi organization WotanJugend (which had also moved to Kyiv. Ed.). It was a two-hour-long conversation of academic nature, extremely respectful, in which people from both sides of the frontline were discussing where a Russian nationalist should be. Each of them was arguing their point. Vikhorev said that there was a Russophobic communist regime in Russia, while Milchakov argued that the Russian side had something closer to the ideals of their youth, to a reich in some form. These are purely matters of taste, even when it comes to geopolitics,” claims Ragozin.

Music, football and ratlines

The mass exodus of Russian Nazis to Ukraine would be impossible without the existing international Nazi network which formed in post-Soviet countries along the axis of Ukraine—Belarus—Russia long before the 2014 events. It was built on two subculture elements which still play a major role in the organization of far-right infrastructure: football and concerts.

“I would not make a clear distinction between Russian and Ukrainian Nazis, because it is a shared milieu which, before the Maidan, migrated across the border with absolute freedom and exchanged ideas. For instance, Olena Semeniaka from the Azov movement hung out with Duginists and attended Dugin’s seminars in Moscow suburbs. As for the Nazis themselves, there was a lot of mutual movement before the Maidan, mainly associated with concerts by far-right bands or with football games. In football fan circles, there was a very important partnership between the fans of Ukrainian and Russian teams which were always in pairs. These were CSKA Kyiv and CSKA Moscow, as well as Metallist Kharkiv and Spartak Moscow. That is, the neo-Nazi fan groups which existed in Russia usually had a partner in Ukraine and opposed similar Russian-Ukrainian fan pairs,” noted Leonid Ragozin.

Participation in fan groups is a traditional recruiting tool for the far right. One of the leaders of this subculture in Ukraine was the Russian Nazi Denis Kapustin, who moved to Ukraine in 2017. He is also associated with the athletic aspect of the Nazi infrastructure: martial arts, MMA clubs, hand-to-hand combat tournaments, the White Rex clothing brand which he has lately been trying to reboot.

According to Ragozin, Olena Semeniaka and Denis Kapustin are important from the perspective of integration of Ukrainian and Russian Nazism into the broader pan-European Nazi movement. “Kapustin is well-known everywhere, he frequently moves between countries. He brings to Kyiv the culture which didn’t used to be typical for Russian and Ukrainian Nazis, but which developed independently of them in Europe,” noted Ragozin in a conversation with The Marker.

“As for concerts, these were mainly guest performances by Russian Nazi bands. For instance, if you look at the history of the Russian-Ukrainian band the Hammer of Hitler (or M8l8th, led by Alexey Levkin, the leader of the WotanJugend movement. Ed.) or examine the concert history of any Nazi band that existed in the late 2000s or the early 2010s, you will see travelling between Russia and Ukraine, performances in Ukraine, especially in Kharkiv. When you talk to the Nazis themselves, it turns out that they frequently attended those concerts. One example is Roman Zheleznov (a.k.a. ZyXEL. Ed.) whom I have talked to. He claimed that he was not a football fan, and his communication with the Ukrainians was associated specifically with the music circles and with trips to concerts in Kharkiv, where the Azov movement later developed in its embryonic form under the name the Little Black Men. Russian Nazis played a key role in it from the get-go,” argues Leonid Ragozin.

Ukraine was discovered in a new capacity, as a place for hiding from law enforcement, by militants from the Russian far-right terrorist group BORN (Militant Organization of Russian Nationzlists) who committed 11 murders in Russia. In 2009, the Nazi Aleksandr Parinov, who murdered an anti-fascist activist, fled to Ukraine. Parinov has still not been punished for his crimes. According to the media, he is currently a member of Azov-adjacent circles.

Russian anti-fascists track the movements of the most infamous militants. The most well-known photo of the BORN murderer Aleksey Korshunov was taken on 24 November 2008 by a member of the anti-fascist movement. The murderer was waiting for his victim, the lawyer Stanislav Markelov, with a gun, but he was spooked by anti-fascists. Two years later, he shot the federal judge Eduard Chuvashov, who was bothering the far-right with his harsh sentences in cases involving Nazi skinhead gangs. Korshunov fled to Ukraine, where he was given shelter by a Kyiv Nazi known as Monia. Markelov was killed in 2009 by BORN members Nikita Tikhonov and Yevgenia Khasis.

“Tikhonov and Khasis hung out in Western Ukraine for a while, their comrade, the Romanian, has been hiding in Ukraine since the mid-2000s, and the former Federal Security Service ensign Aleksey Korshunov from the same gang comically blew up on his own grenade in 2011 while jogging in Zaporizhia. And you can’t even say that the local (Russian. Ed.) far-right were initially younger brothers in this collaboration with the Ukrainian far-right: despite their numbers and direct action, Ukrainian Nazis had incomparably less blood on their hands,” claimed the Moscow anti-fascist Ivan Krasny in a conversation with The Marker.

“Come to Ukraine, you can do anything here!”

The Canadian journalist and Bellingcat writer Michael Colborne is writing a book on the Azov movement which will be published in January 2022. Colborne knows the subjects of his research personally: in November 2018, the far-right beat him up at a transgender rights demonstration in the centre of Kyiv.

“Right now, the main reason for Russian Nazis to move to Ukraine is that they want to escape the current political situation at home. The Putinist regime is not a huge fan of the far-right and does not need them (earlier, the Presidential Administration curated the activities of the National Socialist Society (NSO) and the BORN ideologist Ilia Goriachev, who has been sentenced to life in prison. Ed.). Under these circumstances, they started to realize that Ukraine is a much more suitable country for the extreme right. First of all, it is just nearby. Second, they know it through the old connections between the far-right scenes of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. Third, they view Ukraine as a place where they can express their views freely. Of course, people such as Botsman, who launch recruiting campaigns under the slogan ‘Come to Ukraine, it’s great here and you can do anything!’, are exaggerating somewhat, because there are limits for the Nazis even in Ukraine. However, they can act openly here, which they could only dream of before. Seeing what they perceive as the lack of opportunities in Russia, seeing that they might have problems with the authorities in Russia, at some point Russian Nazis decide, ‘Screw it, I’m going to Ukraine,’” explained Michael Corborne to The Marker.

The secret of Ukraine’s appeal for foreign Nazis is also in the opportunity to act on their propensity to violence, which is at the core of the far-right idea.

“For the far-right, conflict is, to a significant extent, the meaning of their existence. These are people who are just interested in conflict, so they largely don’t care which side to fight on, Ukrainian or Russian. Since Russian Nazis considered themselves to be in opposition to the Putinist regime, many of them chose Ukraine. They call the Putinist regime the enemy and set the goal of liberating Russia from the regime, which they just do not see as Russian,” claims Leonid Ragozin.

After the beginning of the war in 2014 and the establishment of the Azov Battalion, far-right foreigners, particularly from Russia, realized that the role of the far-right and their position in society has changed in Ukraine: they were no longer criticized or controlled by society and even gained a certain heroic flair. Thus, an open environment for the far-right from across the world was created in Ukraine, and Nazis from various organizations rushed to exploit it. Initially as volunteers at the frontline, and later in Azov, to gain experience in building an organizational network.

“Many far-right foreigners still have illusions about Ukraine. They think that any Nazi can come here and hang out, openly demonstrating his political position, which he cannot do at home, and then magically find himself at the frontline. In 2017–2019, the National Corps was actively growing its international connections. I saw all those Germans, Russians, Swedes, Americans, Croatians who were coming here all excited, ‘Wow, you can do so much and you get away with it!’ This is true to an extent, which is a problem, of course, but they have the distorted idea that the situation of 2014–2015 is still continuing. They look at Ukraine and Azov with respect, although in reality, the scale of Azov’s achievements is greatly exaggerated. It’s inflated advertising, a mix of myth and reality,” emphasized Colborne.

Members of the Azov movement themselves contributed a lot to the creation of this myth by actively inviting Western right-wing radicals to visit Ukraine. Since many far-right organizations in Europe look up to Russia, National Corps members make efforts to convince their colleagues to start supporting Ukraine.

Fuhrer Botsman and the mafia state

The Azov Battalion (today the Azov Regiment of the Ukrainian National Guard) was created in 2014 with volunteers, members of the far-right organization Social National Assembly. Over time, the membership of Azov grew, and its role and position shifted. In 2015, the non-governmental organization Azov Civil Corps was established on the basis of Azov; in 2016, a full-fledged political party National Corps emerged from it. The Azov Movement is at the core of the far-right movement in Ukraine, experts say.

“The Maidan produced stable Ukrainian patriotic structures which are mostly Russian-speaking. And the most prominent among them, the Azov Movement, was created by people from Kharkiv, which is to say they were initially Russian speakers. And the Nazis from Russia play a very important role in it, both ideological, in the case of Aleksey Levkin from WotanJugend and, to an extent, Botsman, and economic—in this case the figure of Botsman comes to the forefront as the key capitalist of the Azov Movement. Here, he plays the same role as he played in the Belorusian RNU (Russian National Unity. Ed.) and the Russian NSS (National Socialist Society. Ed.). I would say that the central figure is Sergey Korotkikh, and the rest are secondary,” noted Leonid Ragozin.

After the dismantling of the NSS, Botsman fled to Ukraine and found himself in the Azov Battalion as an instructor, and later as a commander of a reconnaissance company. In just a few months, he received a passport from the hands of then-President Petro Poroshenko. In Ukraine, Botsman found a powerful patron, namely the Internal Affairs Minister Arsen Avakov, and got rich.

He succeeded in this to a large extent due to effective networking. According to Colborne, Botsman set up a network of loyal people affiliated with the far-right movement. “Since I started writing about Azov three years ago, Botsman’s role and activities have changed significantly. I noticed that in 2020–2021, people such as Aleksey Levkin were integrated into Botsman’s orbit. He surrounds himself with a team of Russian Nazis who are hiding in Ukraine, such as Mikhail Shalankevich,” noted the Canadian journalist.

Botsman has a sinister reputation: high-profile murders, of the journalist Pavlo Sheremet and another Azov leader Yaroslav Babych, are linked to him, as well as racketeering, kidnappings, robberies and smuggling. In August 2021, the Investigative Committee of Russia charged Korotkikh with a series of murders motivated by national hatred and arrested him in absentia; however, Botsman was never held accountable by law. Leonid Ragozin uses the term mafia state to describe the impunity of Nazis who have gained immunity from prosecution. In his book, Michael Colborne also describes the far-right in Ukraine as mafia:

“Azov is a big and powerful family. If you want to do business, you need to coordinate your actions with it in some way, which means falling under its influence. If you are a right-wing radical and you want to work in your own niche, you will still have to coordinate with Azov. If you are a right-wing radical and you want to oppose Azov, you are doomed to fail.

“In post-Soviet countries, organized crime and oligarchs act on the same scene. It is possible that the far right’s connections with these groups in Ukraine are fleeting. For instance, they act as infantry, security or hired thugs. Obviously, Russian Nazis in Ukraine are supported by a certain power and receive money from it, but this connection is opaque, it’s a window with the shades drawn. We want to come closer and look, maybe we’ll see some shadows sneaking here and there, we can even assume that they belong to certain figures, but the truth is that we don’t know.”

The Great Schism 2.0

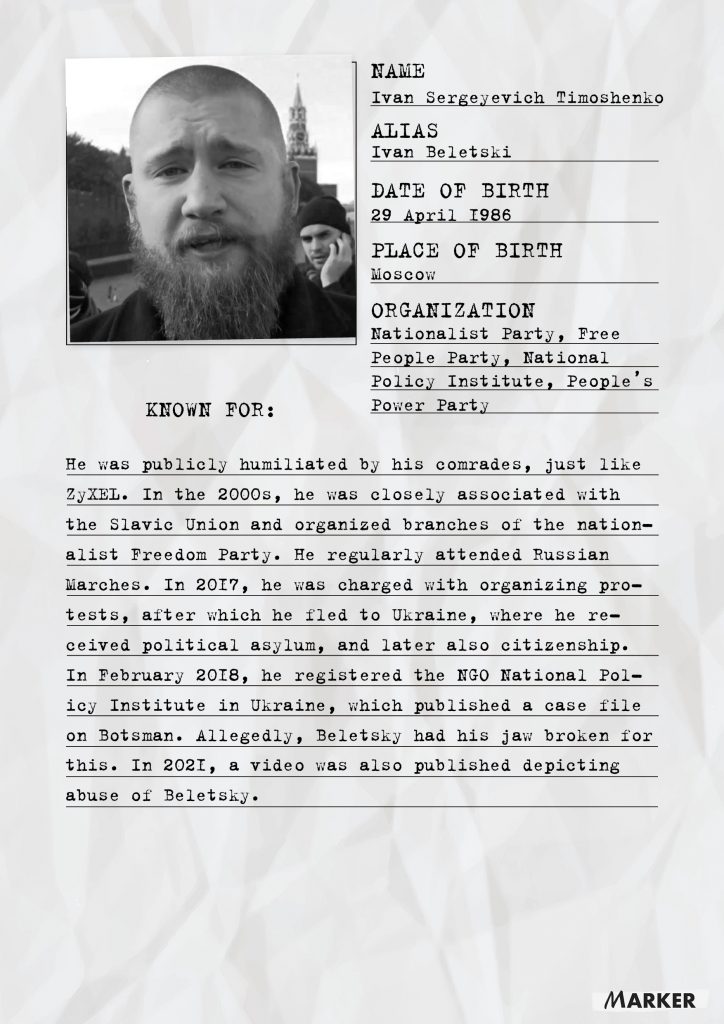

Even though Botsman is feared in Ukraine, his former associates from the Azov Movement, Honor from Kyiv and a new right radical Ivan Beletsky from Moscow, who received Ukrainian citizenship in 2019, have openly confronted him. Beletsky declared that Botsman can use him to eliminate his hitman, a Voronezh Nazi Artem Krasnolutski. And one of the most high-profile exposes of Botsman was a video by the ATO veteran, liberal nationalist and blogger Valeriy Markus.

According to Leonid Ragozin, the conflict between the Nazi groups reflects an opposition between Ukrainian law enforcement structures and oligarchic clans that use the far right for physical confrontations with their opponents from the pro-Russian camp.

According to Colborne, disagreements are also brewing within Azov, which is fraught with much more serious consequences. “In 2020–2021, the Azov Movement experienced a kind of existential crisis. ‘Alright, we’ve been doing this for 6–7 years. What are we going to do next? Will the vector of our development continue to be determined by Biletski and his Patriot of Ukraine? Will we go mainstream?’ My sources have reported friction between Botsman and the Azov commander Andriy Biletski. In addition, there are people within the movement who are more impatient and want to become harsher and disregard the public opinion. For instance, attack LGBT+ people, beat up people drinking alcohol in the streets, like Mikhail Shalankevich and his Alternative does. It will only get worse over time. The leaders of today are getting older, they are in their 30s or 40s, but there are many young activists, teenagers who haven’t even turned 20. They seek radical action. Then something very bad will happen,” cautions Colborne.

Gray zone for the Brownshirts

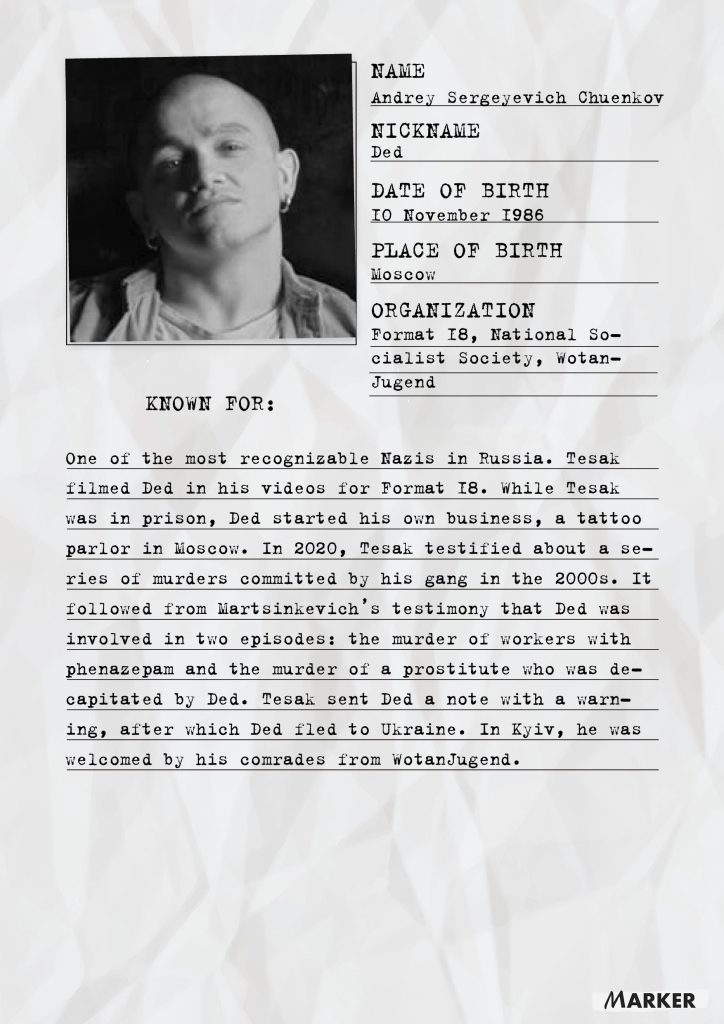

The main wave of Russian Nazi migration to Ukraine took place in 2014–2015. The last high-profile case was in the autumn of 2020, when Andrey Chuenkov, Tesak’s comrade and a member of WotanJugend, fled to Ukraine. According to the Sova Think Tank, about 100 far-right activists from Russia are currently in Ukraine. Experts surveyed by The Marker give similar numbers. Most of those who participated in the hostilities left Eastern Ukraine after the active stage of the conflict ended.

“It’s in decline. Far-right Russians see the difficulties faced by their friends in Ukraine. They cannot legalize their status for many years, even though they fought for Ukraine and received awards. Many of them can’t obtain a residence permit or Ukrainian citizenship,” claims Leonid Ragozin.

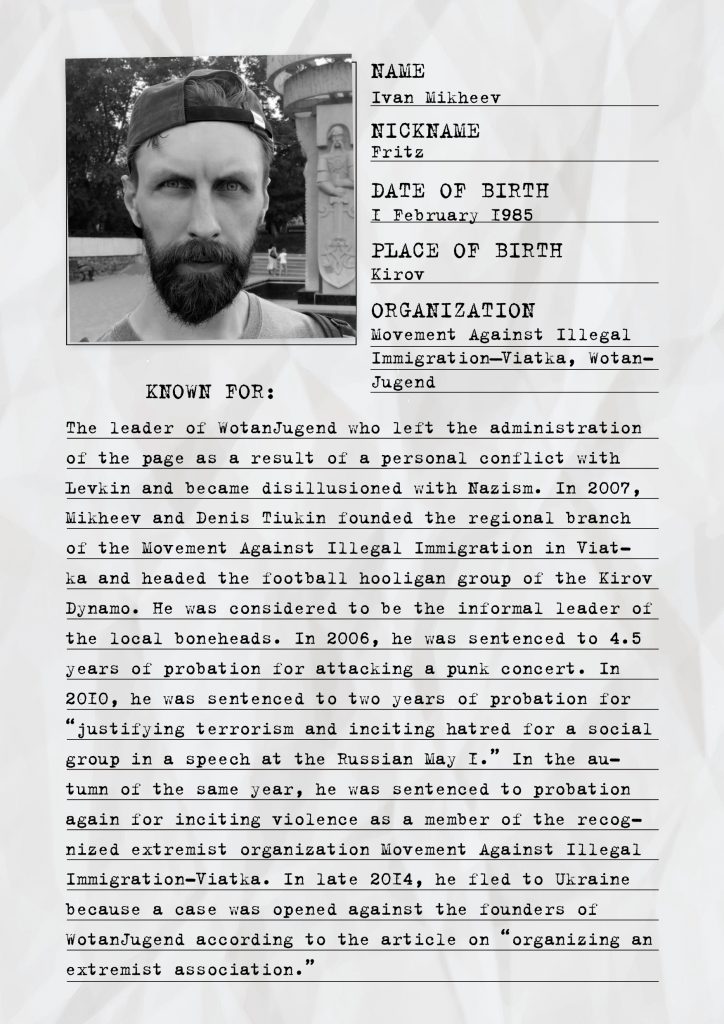

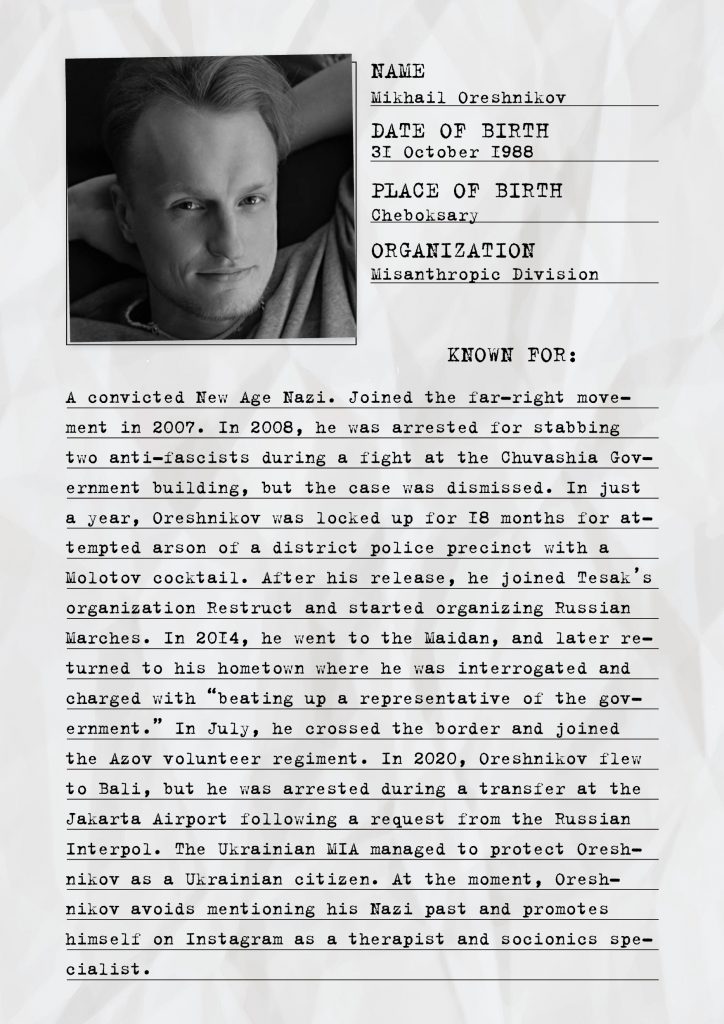

One of the founders of WotanJugend, the Nazi Ivan Mikheev, moved to Ukraine in 2014 as a political refugee. However, the authorities denied him status and he stayed in Kyiv in an undetermined situation. He has even blamed his former WotanJugend comrade Aleksey Levin for his misadventures, writing an entire Saga on Dark Ungratefulness. Meanwhile, another Russian Nazi, a Misanthropic Division member Mikhail Oreshnikov, was given political asylum by Ukrainian authorities in 2014, and then received citizenship.

“The Russian Nazis are living in the ‘grey zone.’ Many of them live in Ukraine illegally, but they are unlikely to be deported. Azov veterans have been trying for years to get a law passed to give citizenship for their volunteers. The far-right fighter Nikita Makeev received Ukrainian citizenship by Zelenski’s order. Before this, he had to jump at Poroshenko’s car. I’m not sure that Zelenski is prepared for the international backlash that may follow if he gives out passports to people such as Levkin or Denis Kapustin, who aren’t even veterans. And Russian Azov veterans are going to wait indefinitely,” says Michael Colborne with confidence.

According to Leonid Ragozin, the political situation around the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has been frozen, so the status quo of Russian Nazis in Ukraine remains the same. And the Ukrainian authorities are completely fine with this situation, just like with the situation of the far-right in general. The resignation of the Internal Affairs Minister Arsen Avakov in July 2021 could have stirred political processes in Ukraine and deprived the Nazis of immunity from prosecution, but the law enforcement limited themselves to targeted arrests in August and September 2021.

“After the August murder of Vitaliy Shyshov, the chairman of the NGO Belarusian House in Ukraine, there was a feeling that the Security Service was trying to launch an attack on the Azov Movement. There were arrests of very important figures in Kharkiv, the homebase of the Azov Movement. But this was not followed up by anything, because everyone was waiting to see what would happen to Botsman, but nothing happened to him. And this is a sign of his power and influence on government and law enforcement structures in Ukraine,” says Leonid Ragozin.

The director of the investigative film Credit for Murder, about a 2007 double murder in Russia which was allegedly committed by Botsman, hinted in late August that Korotkikh could have fled the country. This information has neither been confirmed nor disproven. It should be noted that Botsman was last seen in public on 19 August. His YouTube channel has stopped doing live streams, although Botsman’s Telegram is updated daily. On 10 October, Botsman published a video from the Standfort shooting club in Kyiv, but there is no indication as to when the video was recorded.

Michael Colborne is also convinced that nothing will change after Arsen Avakov’s resignation: “The far-right will be held accountable for violence in individual cases, but there will be no large-scale campaign against them. There will be no dismantling of the far right in Ukraine.”

The Russian Nazis who fled to Ukraine found themselves trapped by their own ideas. There is no way back: prison awaits there. Legalizing and obtaining citizenship in Ukraine is hard, you need connections and patronage for that. Reconquista or a liberation war never happened: the hot stage of the conflict is over. The Russian expats, except for a few isolated individuals, have found themselves playing “the role of cheap mercenaries, or even just so-called useful fools,” as Ivan Mikheev bitterly admits. Thus, in a situation of total acquiescence by the authorities and the lack of opportunities to properly earn a living, deprived of the usual social connections and locked in a foreign land, the Russian Nazi is compelled to do what he does best—violence and crime.